A Comprehensive Guide to Basic Chinese Grammar [ with Rules and Sentence Structure]

Some people say Chinese grammar is complicated, and some foreigners think Mandarin Chinese has no grammar… So what are the facts about Chinese grammar? Basic Chinese grammar is not difficult – seriously! The truth is that Chinese grammar is unique.

The Chinese language has its unique characteristics and a great deal of flexibility in grammar. If you’ve studied other languages before, you’ll find that learning Chinese grammar isn’t a typical language learning experience, and there may be a lot of new concepts that you’ve never heard of.

We’ll prove it to you by listing all the key Chinese grammar points you need to know. In this article, we will not only provide basic Chinese language grammar, but we will also give many Chinese sentence examples and rules about sentence structure to help you consolidate your knowledge.

Let’s dive in!

Basic Features of Chinese Grammar

If you have studied common Romance languages such as Spanish or French, you may have wondered how Chinese deals with headache-inducing grammatical problems such as verb conjugation.

Fortunately, these grammatical headaches are almost completely absent in Mandarin Chinese. There are similarities and differences between Chinese and English grammar. The most basic grammatical structures are the most obvious examples of why Chinese grammar is so easy to learn. Here are some unique and simple things to know about basic grammar:

1. Subject verb object

At the most basic level, Chinese sentence structure is strikingly similar to English. Like the English language, many basic Chinese sentences use either subject-verb or subject-verb-object structures. For example sentences:

In the following sentence, the subjects are “她” (tā, she) and “我” (wǒ, I), and the verbs are “去” (qù, go) and “吃” (chī, eat).

Subject-Verb:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我吃。 | Wǒ chī. | I eat. |

| 她去。 | Tā qù | She goes. |

Subject-Verb-Object:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我去超市。 | Wǒ qù chāo shì. | I go to the supermarket. |

| 她吃面包。 | Tā chī miàn bāo. | She eats bread. |

| 你喜欢猫。 | Nǐ xǐ huān māo. | You like cats. |

2. Time and place

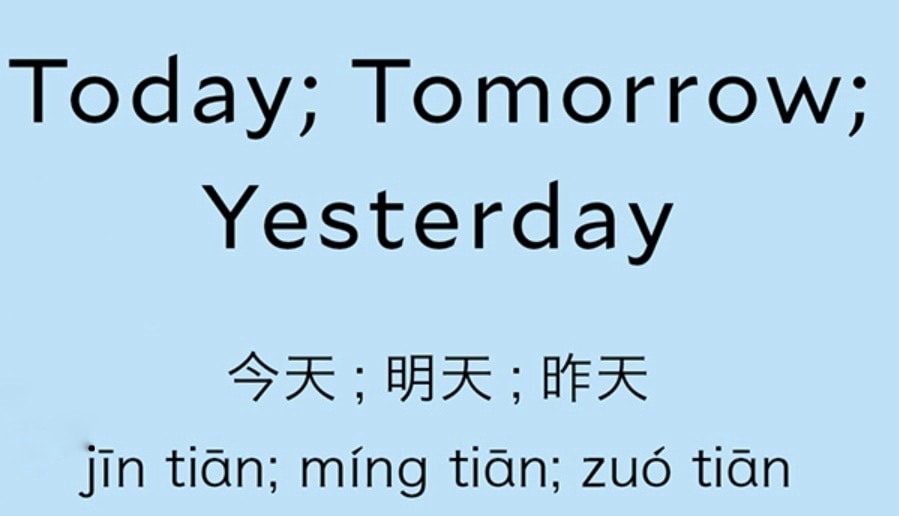

In Chinese, the time at which something happened, is happening, or will happen appears at the beginning of the sentence or immediately following the subject.

In the first sentence below, both the Chinese time word “昨天” (zuótiān) and the English “yesterday” appear at the beginning of the sentence.

However, in the second example, the Chinese time word appears after the subject (他 tā), while the English time word appears at the end of the sentence.

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 昨天他去了公园。 | Zuó tiān tā qù le gōng yuán. | Yesterday, he went to the park. |

| 他昨天去了公园。 | Tā zuó tiān qù le gōng yuán. | He went to the park yesterday. |

Place words in Chinese also generally require a different word order than in English.

When describing where something happened, you usually need to construct a phrase or a sentence starting with the Chinese character “在” (zài). Your “在” phrase should come after the time word (if any) and before the verb. This can be confusing to English speakers because, in English, positional words usually appear after (not before) verbs.

Here are the examples:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我在北京工作。 | wǒ zài běi jīng gōng zuò. | I work in Beijing. |

| 我昨天在家看书。 | wǒ zuó tiān zài jiā kàn shū. | I read books at home yesterday. |

However, keep in mind that there are exceptions to this rule. These exceptions occur with certain verbs used to refer to directional movement, such as “走” (zǒu, “go”), or verbs associated with a specific location, such as “停” (tíng, “stop”) and “住” (zhù, “live”).

Such verbs are allowed to take location complements, which are essentially “在” phrases that come after the verb. For example:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我住在北京。 | wǒ zhù zài běi jīng. | I live in Beijing. |

Verbs with location complements are the exception, not the rule. As a beginner in Chinese grammar, the safest thing to do is to put the location before the verb, as this is the most common word order.

3. Plural and singular

Many English nouns have both singular and plural forms. For example, you can say you have “one dog”, but if you have two or more, you must add an “s” to the noun to indicate the plural.

This is not the case in Chinese. Whether you have one, two, or two thousand of something, the noun you use to describe it is the same.

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我有一个问题。 | Wǒ yǒu yīgè wèntí. | I have a problem. |

| 我有两个问题。 | Wǒ yǒu liǎng gè wèntí. | I have two problems. |

| 我有十个问题。 | Wǒ yǒu shí gè wèntí. | I have ten problems. |

Please note that the Chinese word for “problem” – “问题” (wèntí) does not change, no matter how many problems you have.

In addition, the Chinese language also has a suffix – “们” (men) – that can be added to some words to indicate pluralization, but it is limited to certain pronouns and words that refer to people.

For example, the plural form of “他” (tā) is “他们” (tāmen). If you want to refer to a group of people rather than a single person, you can also use 他们.

Consider the following examples:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我们 | wǒmen | we |

| 他们 | tāmen | they (all male or mixed gender group) |

| 她们 | tāmen | they (female group) |

| 你们 | nǐmen | you (plural) |

| 学生 | xuéshēng | student |

| 学生们 | xuéshēngmen | students |

| 老师 | lǎoshī | teacher |

| 老师们 | lǎoshīmen | teachers |

| 孩子 | háizi | child |

| 孩子们 | háizimen | children |

| 女士 | nǚshì | lady |

| 女士们 | nǚshìmen | ladies |

| 先生 | xiānshēng | gentleman |

| 先生们 | xiānshēngmen | gentlemen |

| 朋友 | péngyǒu | friend |

| 朋友们 | péngyǒumen | friends |

4. No noun-adjective gender agreement

As you start to learn more Chinese vocabulary, you will learn a lot of nouns. These words will form the subjects and objects of the sentences you learn. In Chinese, as in English, adjectives do not have to agree in gender or number with the nouns they modify. For example, in French, if a noun is feminine, its corresponding adjective must also be feminine.

Chinese adjectives do not have this variation. Unlike adjectives in many European languages, Chinese adjectives don’t change depending on whether the noun they modify is plural or singular, either.

5. No verb conjugation or tenses

One of the more peculiar aspects of Chinese grammar is the complete lack of verb conjugation.

In English, the third-person singular (he/she/it/one) form of a verb is often different from the other forms. So if the subject is “I”, we say “I go“, but if the subject is “he”, we say “he goes“.

In Chinese, there is no such variation. Whether we say “我去” (wǒ qù) or “他去” (tā qù), the verb “去” (qù, “to go”) is the same. A fact about Chinese is that the Chinese verb stays the same no matter what the subject of the sentence is.

Observe how the verb 吃 (chī, “to eat”) stays the same in all of the following sentences:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我吃面包。 | Wǒ chī miànbāo. | I eat bread. |

| 你吃面包。 | Nǐ chī miànbāo. | You eat bread. |

| 他吃面包。 | Tā chī miànbāo. | She eats bread. |

| 我们吃面包。 | Wǒmen chī miànbāo. | We eat bread. |

| 他们吃面包。 | Tāmen chī miànbāo. | They eat bread. |

Another interesting aspect of grammar in the Chinese language is that Chinese does not have verb tenses. In most Romance and Germanic languages, including English, whether something happened in the past, present, or future is indicated primarily through verb tenses.

In contrast, Chinese uses more grammar. Verbs in Chinese always remain the same and do not need to be conjugated. To express time frame in Chinese, you can use the following Chinese words:

- 了 (le)

- 过 (guò)

- 着 (zhe)

- 在 (zài)

- 正在 (zhèngzài)

The time frame can also be expressed by a specific reference to a point or period, for example:

- 明天 (míngtiān, “tomorrow”)

- 昨天早上 (zuótiān zǎoshang, “yesterday morning”)

- ……的时候 (……de shí hòu, “when…”)

These time markers can be confusing for beginners, so don’t worry if it takes some time to master them. Here are a few examples to give you a basic idea of how they work:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 他去学校了。 | tā qù xué xiào le. | He went to school. |

Notice how the verb 去 (qù, “to go”) is left unchanged and unconjugated. The marker 了 (le) is added to the end to indicate past tense.

The following example also uses the verb “去” (qù, to go), but again, there is no conjugation of the verb itself. Instead, the time marker “过” (guò) is used to indicate that the event has begun and ended:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 她去过。 | tā qù guò. | She has been there. |

In the following examples, the verb “工作” (gōngzuò, “to work”) is preceded by “在” (zài) to indicate that the action of working is continuous.

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我在工作。 | wǒ zài gōng zuò. | I’m working. |

Keep in mind that although 在 (zài), 正在 (zhèngzài), and 着 (zhe) are roughly equivalent to the English “-ing” in many contexts, they are generally not interchangeable and have different usages and nuances.

6. Asking questions

Asking basic questions in Chinese is also easy. The easiest way to ask a question is to add “吗”(ma) at the end of a sentence. This method can be used to turn a statement into a yes or no question.

Statement sentence:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 你要去学校。 | nǐ yào qù xué xiào. | You want to go to school. |

| 他喜欢小狗。 | tā xǐ huān xiǎo gǒu. | He likes puppies. |

Yes or no question sentence:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 你要去学校吗? | nǐ yào qù xué xiào ma? | Do you want to go to school? |

| 他喜欢小狗吗? | tā xǐ huān xiǎo gǒu ma? | Does he like puppies? |

For more complex questions, Chinese also has question words similar to English. Here is a list of question words in Chinese:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 谁 | shéi | who |

| 什么 | shénme | what |

| 哪里 | nǎlǐ | where |

| 为什么 | wèishéme | why |

| 哪个 | nǎge | which |

| 什么时候 | shénme shíhòu | when |

| 怎么 | zěnme | how |

Note that the word order of Chinese questions is different from English, so you may not be able to use all Chinese questions correctly right away. However, it is not difficult to learn how to ask questions, and you can start by using the “吗” (ma) sentence.

7. Negation

Negation is another important point of basic Chinese grammar that beginners must master. The Chinese use two different ways to express negation. The most common is the use of the character “不” (bù), which roughly means “no”, “won’t” or “don’t want”. For example:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 这件衣服不好看。 | zhè jiàn yī fú bù hǎo kàn. | This dress does not look good. |

| 我不要去超市。 | wǒ bú yào qù chāo shì. | I do not want to go to the supermarket. |

| 她不吃苹果。 | tā bù chī píng guǒ. | He does not eat apples. |

The word 不 (bù) can be used in most cases. However, 不 (bù) should never be used with the verb 有 (yǒu, “to have”).

If the sentence you want to negate contains the verb 有 (yǒu), then you must use 没 (méi) together to indicate negation. Here are some examples:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我没有猫。 | Wǒ méiyǒu māo. | I do not have any cats. |

| 他们没有面包。 | Tāmen méiyǒu miànbāo. | They do not have any bread. |

8. Measure words

As an English speaker, you already know how to use measure words (also known as “classifiers”), which are more common in English. For example, we often say a “pair” of pants or a “slice” of cake. Both “pair” and “slice” are measure words.

One of the main differences between English and Chinese measure words is that there are much more of them in Chinese. In addition, every noun in Chinese must be preceded by a measure word, whereas in English, only some nouns require measure words.

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | English |

|---|---|---|

| 我有一条狗。 | wǒ yǒu yī tiáo gǒu. | I have a dog. |

| 他喜欢这本书。 | tā xǐ huān zhè běn shū. | He likes this book. |

Moreover, “个” (gè) is the most commonly used Chinese measure word, so if you choose to use it when you’re unsure, you’ll probably get lucky and make a correct sentence! Don’t worry. Even if you use it incorrectly, people usually understand what you mean. Here are a few common Chinese measure words:

| Chinese | Pīnyīn | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 个 | gè | most common measure word |

| 只 | zhī | measure word for animals |

| 本 | běn | measure word for books |

| 辆 | liàng | measure word for vehicles |

| 块 | kuài | measure word for pieces of objects and for money |

| 封 | fēng | measure word for letters |

| 张 | zhāng | measure word for flat objects, like paper |

| 瓶 | píng | measure word for bottles |

| 杯 | bēi | measure word for cups |

| 双 | shuāng | measure word for pairs (of things) |

The Most Basic Chinese Sentence Structures

Now that you are familiar with the basic elements of Chinese grammar, let’s take a look at the most common sentence structures in Chinese and some examples.

1. Subject + Verb + Object (SVO)

The most basic grammatical structure in English is also the most basic grammatical structure in Chinese. You are accustomed to starting with a subject, then a verb, and finally an object. In other words, the structure of the sentence is “Who does what”.

Here are some examples:

- I study Chinese. — 我学习中文。 (wǒ xué xí zhōng wén)

- Mom eats fruit. — 妈妈吃水果。 (mā ma chī shuí guǒ)

- I love Shanghai. — 我爱上海。 (wǒ ài shàng hǎi)

2. Subject + Time + Verb + (Object)

The next sentence pattern adds the element of time. As you learned earlier in this article, time always appears at the beginning of a sentence, usually immediately after the subject. This will help you immediately identify when something happened, thus eliminating the need to conjugate verbs.

- I will rest today. — 我今天会休息。 (wǒ jīn tiān huì xiū xi)

- She studies Chinese in the mornings. — 她早上学习中文。 (tā zǎo shàng xué xí zhōng wén)

- I watched a movie yesterday. — 我昨天看了一部电影。 (wǒ zuó tiān kàn le yí bù diàn yǐng)

3. Subject + Time + Location + Verb + (Object)

You can add the location of an action by using the preposition 在 (zài) followed by the location right before the main verb of the sentence.

Here’s what that looks like:

- We will meet at the door tomorrow. — 我们明天在门口见面。(wǒ men míng tiān zài mén kǒu jiàn miàn)

- My sister will compete in the sports field today. — 我妹妹今天在运动场比赛。(wǒ mèi mei jīn tiān zài yùn dòng chǎng bǐ sài)

4. Subject + Time + Location + Verb + Duration + (Object)

This is the longest of the basic sentence structures and it allows you to express a great deal of information without using any complex grammatical structures. Here are a few examples:

- I studied in the library for six hours yesterday. — 我昨天在图书馆学了六个小时。 (wǒ zuó tiān zài tú shū guǎn xué le liù gè xiǎo shí)

- Dad will work ten hours in the office tomorrow. — 爸爸明天在办公室会工作十个小时。 (bà ba míng tiān zài bàn gōng shì huì gōng zuò shí gè xiǎo shí)

- I exercise in the gym for forty-five minutes every day. — 我每天在健身房锻炼四十五分钟。 (wǒ měi tiān zài jiàn shēn fáng duàn liàn sì shí wǔ fēn zhōng)

5. The 把 (bǎ) Sentence

The “把” (bǎ) sentence is a useful structure for making long sentences. The focus of the “把” (bǎ) sentence is on the action and its object.

This is a very common sentence pattern in Chinese, but it can feel a bit strange to English speakers (at least at first). Like English, basic sentences in Chinese are formed using the subject-verb-object (SVO) word order:

Subject + [verb phrase] + object

In a “把” (bǎ) sentence, things are changed and the structure goes like this:

Subject + 把 (bǎ) + object + [verb phrase]

Now we can see that the object has moved, it is preceded by “把” (bǎ), and the order is SOV. So why use this somewhat strange (at least strange to English speakers) sentence?

Although you may think you’ll never use “把” sentences, they’re still handy. Let’s look at the following example:

把笔放在桌子上。(bǎ bǐ fàng zài zhuō zi shàng) — Put the pen on the table..

What to say if you don’t use the “把” structure? You might say it like this: 笔放在桌子上。(bǐ fàng zài zhuō zi shàng)

Although this sentence is grammatically correct, the meaning may change. 笔放在桌子上 (without 把, bǎ) can mean the same thing, but it could also mean “The pen is on the table”. It is the answer to two questions: (1) where should I put the pen?, and (2) where is the pen?

The 把 (bǎ) sentence is clearer. 把笔放在桌子上 is a command; you are telling someone to put the pen on the table. There is less room for confusion.

General Rules for Chinese Grammar

While it is important to learn grammatical details in small chunks, it is also very useful to familiarize yourself with some general Chinese grammar rules. These are not specific grammatical structures, but general facts about Chinese that apply in most situations. They can help you understand Mandarin Chinese and how it works.

Rule 1: What precedes modifies what follows

This rule may seem a bit complicated, but it’s very simple. It simply means that the modifier comes before the thing being modified. The Chinese language has always had this rule, from ancient texts to modern vernaculars.

Let’s take a few simple examples to illustrate this rule.

- He doesn’t like expensive things. — 他不喜欢贵的东西。(Tā bù xǐhuan guì de dōngxi)

- My brother drives slowly. — 我哥哥慢慢地开车。(Wǒ gēgē mànmande kāichē)

- She can drink a lot of beer. — 她能喝很多啤酒。(Tā néng hē hěnduō píjiǔ)

As you can see, in each Chinese sentence, the modifier comes before the thing it modifies. 贵的 (expensive) comes before 东西 (thing), 慢慢地 (slowly) comes before 开车 (drive), and 很多 (a lot) comes before 啤酒 (beer). Notice how the position of the modifier changes in the English sentence.

Knowing the “modifiers come first” rule in Chinese grammar is very helpful in the early stages of learning Chinese. It allows you to master sentence structure faster because you can more easily identify modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) and the things they modify (nouns and verbs).

Rule 2: Chinese is topic-prominent

This is a rule that English speakers often have trouble getting used to. Chinese is a topic prominent. This means that it puts the thing that the sentence is about first. English, on the other hand, is subject salient, which means that it puts the actor in the sentence (the subject) first.

For instance, I’ve finished my work.

In this simple sentence, the subject is “I”, but that is not really the point of the sentence. The subject of the sentence is not the speaker, but the job. So the subject of this sentence is “work”.

Because the Chinese language is topic-first, it is usually possible and very natural to put the topic, rather than the subject, first in a sentence. However, it is possible to do this in English, but it sounds less natural, as you can see in the following example:

- 香蕉我不太喜欢。(xiāng jiāo wǒ bù tài xǐ huān) — Bananas, I don’t really like.

- 美国我没去过。 (měi guó wǒ méi qù guò) — America, I haven’t been to.

According to Chinese grammar rules, the above sentence is perfectly fine to use, but it is very strange in English. Please note that you can also put the subject in front of it so that the Chinese sentence is also grammatically correct.

Rule 3: Chinese is logical

Finally, let’s talk about the most general rules of Chinese grammar. One of the joys of learning Chinese is that it is a very logical and consistent language. This is very true of Chinese vocabulary, as you can usually see the logic behind most words very clearly. The same is true of Chinese grammar rules, which tend to be consistent and reusable once you’ve learned them.

One example of this is that Chinese tends to be expressed only once in a sentence. For example, if time has already been stated clearly, it does not need to be indicated again. Similarly, the number of a noun only needs to be indicated once in most cases. As you learn the language, these examples will become more and more common. Keep this in mind, and you will often find yourself able to guess more accurately how new things are expressed in Chinese.

FAQs on Chinese Grammar

1. How does Chinese grammar compare to English grammar?

Answer:

- Similar Word Order: Both use SVO structure

One of the most comforting aspects of Chinese grammar for English speakers is that both languages follow the subject-verb-object (SVO) structure. This means that a sentence like “I eat apples” in English can be directly translated into “我吃苹果。” in Chinese with the same word order.

- No Articles: Forget about “A” or “The”

One major difference is that the Chinese do not use articles such as “a” or “the”. Instead, quantifiers or context can indicate whether you are referring to something specific or general.

- Simplified Verb Usage: No tense conjugation

Unlike verbs in English, which change form according to tense (e.g., “go” vs. “went”), verbs in Chinese remain unchanged. Instead, time is expressed through time words or context.

2. How do you say “grammar” in Chinese?

Answer: Grammar in the Chinese language is 语法 (yǔfǎ).

3. Is Chinese grammar easy?

Answer: Chinese grammar can be a bit confusing at first, but it is much simpler than the grammar of other languages!

Once you understand the basic structure, Chinese grammar is easy to use.

Conclusion

Learning Chinese grammar doesn’t have to be a daunting task. By mastering the effective information given in this article, you will find your journey to Chinese grammar mastery both rewarding and fun.

We hope that this article has helped you gain a basic understanding of Chinese grammar and that you are ready to learn more! If you are interested in expanding your mastery of the basics of Chinese, you can also take the WuKong Chinese course. We hope your Chinese learning journey is fun!

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!Master’s degree from Yangzhou University. Possessing 10 years of experience in K-12 Chinese language teaching and research, with over 10 published papers in teh field of language and literature. Currently responsible for teh research and production of “WuKong Chinese” major courses, particularly focusing on teh course’s interest, expansiveness, and its impact on students’ thinking development. She also dedicated to helping children acquire a stronger foundation in Chinese language learning, including Chinese characters, phonetics (pinyin), vocabulary, idioms, classic stories, and Chinese culture. Our Chinese language courses for academic advancement aim to provide children with a wealth of noledge and a deeper understanding of Chinese language skills.

![Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide] Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/school-2353406-520x293.jpg)

![Chinese Courses Near Me: 5 Best Platforms [Offline & Online] Chinese Courses Near Me: 5 Best Platforms [Offline & Online]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/image-125-1024x682-1-520x293.png)

![200 Celsius to Fahrenheit: How to Convert 200 C to F [Solved] 200 Celsius to Fahrenheit: How to Convert 200 C to F [Solved]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/image-617-520x293.png)

Comments0

Comments