Is Chinese and Mandarin the Same? Key Differences Explained

Many people think Chinese and Mandarin are the same language. But the fact is: they are technically NOT the same thing.

“Chinese” ≠ Mandarin: While Mandarin dominates, dialects like Cantonese retain cultural pride. Hong Kong’s films and music industry, for example, rely on Cantonese.

Mandarin is a form of the Chinese language. There are many different versions of Chinese spoken throughout China, and they are usually classified as dialects.

China has over 200 dialects, including Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghainese, and numerous local languages specific to smaller regions. Mandarin is just one of them.

Are Chinese and Mandarin the Same Language?

Mandarin (like ‘Putonghua’) is the main ‘shared language’ Chinese speakers use in schools, TV, and across China – it’s how everyone understands each other, even if their hometown dialect (like Cantonese) sounds different.

Imagine: All dialects are siblings, but Mandarin is the one everyone learns to talk together!

So no – they’re not the same, but Mandarin is the ‘common voice’ of the Chinese language family.”

What is mandarin Chinese language ?

Mandarin is the official language of China, just as English is in the United States.

Mandarin Chinese, known natively as Putonghua (普通话, “common speech”), is the official language of China and the most widely spoken variety of Chinese globally. Serving as the linguistic backbone of the nation, it unites over 1.4 billion people across a vast and culturally diverse territory.

Mandarin’s dominance extends beyond mainland China to Taiwan and Singapore, where it holds co-official status, and it thrives in overseas Chinese communities worldwide. With approximately 1.1 billion native speakers, it is the world’s most spoken first language, surpassing even English in sheer numbers.

Key Features of Mandarin Chinese

- Tonal Language System

Mandarin is a tonal language, where pitch variations define word meanings. It uses four primary tones and a neutral tone:- First tone (flat, high pitch): mā (妈, “mother”).

- Second tone (rising pitch): má (麻, “hemp”).

- Third tone (falling-rising pitch): mǎ (马, “horse”).

- Fourth tone (sharp falling pitch): mà (骂, “scold”).

- Neutral tone (light, unstressed): ma (吗, question particle).

Mispronouncing tones can lead to confusion—for example, shī (狮, “lion”) versus shǐ (屎, “feces”).

- Logographic Writing System

Mandarin employs Chinese characters, logograms that represent meanings rather than sounds. While all Chinese dialects share this script, two forms exist:- Simplified characters: Adopted in mainland China (1950s) to boost literacy.

- Traditional characters: Retained in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and many diaspora communities.

The Pinyin system, using Roman letters, standardizes pronunciation and aids learners.

- Standardized Structure

Mandarin follows strict grammatical rules, prioritizing word order (subject-verb-object) and context over verb conjugations or plurals. For instance:- 我喝水 (Wǒ hē shuǐ, “I drink water”).

- 他喝水 (Tā hē shuǐ, “He drinks water”).

Particles like le (了) indicate tense shifts: 我吃饭 (Wǒ chī fàn, “I eat”) vs. 我吃饭了 (Wǒ chī fàn le, “I ate”).

- Cultural and Historical Roots

Modern Mandarin evolved from Guanhua (官话, “official speech”), the dialect used by imperial bureaucrats during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Its standardization in the 20th century drew heavily from the Beijing dialect, chosen for its political and cultural centrality.

How did Mandarin become the official language in China?

- Linguistic Unity in a Multilingual Nation

China is home to 292 living languages and dozens of mutually unintelligible dialects, such as Cantonese (spoken by 80 million) and Shanghainese (14 million). Historically, fragmented communication hindered governance and cultural cohesion. Mandarin’s promotion as a national standard, beginning in the 1950s, aimed to bridge these divides. - Government Policy and Education

In 1956, the Chinese government launched a nationwide campaign to popularize Putonghua through:- Mandatory education: Schools teach Mandarin as a core subject, often penalizing dialect use.

- Media control: State TV, radio, and films exclusively use Mandarin, marginalizing regional languages.

- Public signage and documents: All official texts are written in standardized Mandarin.

- Economic and Social Mobility

Proficiency in Mandarin is tied to career advancement, higher education, and access to resources. Rural migrants, for instance, must learn Mandarin to secure urban jobs, accelerating its adoption. - Global Influence and Soft Power

As China’s international clout grew, Mandarin became a tool of diplomacy and trade. Confucius Institutes worldwide promote Mandarin, while businesses prioritize Chinese-language skills. In 2020, the UN designated Mandarin as one of its six official languages, cementing its global relevance.

If you are interested in this area, we highly recommend WuKong Chinese to help you learn the Chinese Mandarin language step by step!

What Is The Difference Between Chinese And Mandarin?

Chinese = a big language family (like Cantonese, Shanghainese dialects). Mandarin (Putonghua/Guoyu) is the main ‘shared language‘ China uses in schools/TV – everyone learns it to understand each other, even if their hometown dialect sounds different.

The terms “Chinese” and “Mandarin” are often used interchangeably, but they represent distinct concepts within the Chinese language family. Below is a detailed analysis that clarifies their relationship while incorporating key geographic, historical, and linguistic elements.

1. Chinese: A Language Family, Not a Single Language

- Chinese language refers to the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan family, encompassing many dialects spoken across China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the Chinese diaspora.

- Dialects spoken include Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese, Shanghainese, Hokkien, and dozens of others.

- These dialects are often mutually unintelligible in spoken form, functioning as completely different languages despite sharing Chinese characters as a written language.

- Key Misconception: Labeling all Chinese varieties as “just dialects” oversimplifies their diversity. For instance, Mandarin and Cantonese differ as much as French and Spanish.

2. Mandarin Chinese: The Official language

- Mandarin Chinese (普通话, Putonghua) is the official language of mainland China and Taiwan, and one of four official languages in Singapore.

- China maintained Mandarin as the national language to unify its linguistically diverse population after the Qing dynasty fell in 1912.

- Based on the Beijing dialect from northern China, it became standard Chinese through government-mandated reforms in the 1950s.

- Geographic Reach:

- Dominates northern China (including the North China Plain) and urban centers nationwide.

- Over 1.1 billion people speak Mandarin as their native language, making it the most widely spoken native language globally.

3. Dialects vs. Mandarin: Coexistence and Conflict

- Major Chinese Dialects:

- Cantonese (Yue): Spoken by Cantonese speakers in Guangdong province, Hong Kong, and overseas communities. Retains Middle Chinese phonology and uses traditional Chinese characters.

- Wu (e.g., Shanghainese): Thrives in southern China, including Shanghai.

- Southern dialects like Hokkien and Hakka: Preserve ancient tones and vocabulary lost in Mandarin.

- Mutual Intelligibility:

- A Mandarin speaker may not understand Cantonese or Shanghainese, even though all share written Chinese.

- Example: The word “hello” is nǐ hǎo (你好) in Mandarin but nei5 hou2 (你好) in Cantonese—same language in writing, different languages orally.

4. Writing Systems: Simplified vs. Traditional

- Simplified Chinese:

- Introduced in the 1950s by the Chinese government to boost literacy. Used in mainland China and Singapore.

- Example: 门 (door) vs. traditional 門.

- Traditional Chinese:

- Retained in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and many diaspora communities. Critical for reading classical texts.

- Unifying Role of Characters:

- Despite spoken differences, Chinese characters allow Chinese speakers from different regions to communicate in writing.

5. Historical and Political Contex

- Qing Dynasty Legacy:

- Mandarin’s predecessor, Guanhua (官话, “official speech”), was used by imperial bureaucrats.

- 20th-Century Standardization:

- The Chinese government promoted standard Mandarin Chinese through schools, media, and laws, marginalizing local dialects.

- Today, ethnic groups in southern China often speak Cantonese or local languages at home but use Mandarin in public.

6. Mandarin vs. Other Chinese dialects

- Mandarin’s Dominance:

- Taught as the primary language in schools nationwide.

- Used in all official contexts, from legal documents to TV broadcasts.

- Regional Resistance:

- In Hong Kong, Cantonese remains central to identity, despite pressure to learn Mandarin.

- In southern China, many speak Cantonese or Shanghainese alongside Mandarin daily.

7. Global Influence and Challenges

- Chinese Diaspora:

- Overseas communities often preserve traditional characters and non-Mandarin dialects. For example, Chinatowns in the U.S. lean on Cantonese speakers.

- Learning Mandarin:

- Non-native learners focus on Mandarin pronunciation and simplified characters for practicality.

- Resources like Pinyin (e.g., mā, má, mǎ, mà) help master its four tones.

Each of the following is described in a number of ways:

| Chinese | Mandarin | |

| what | Hànyǔ(汉语) or Zhōngwén(中文)It is a group of related but in many cases mutually unintelligible language varieties, comprising of seven main dialects: Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, Wu, Min, Xiang, and Gan. | Pǔtōnghuà(普通话)It is a standardized form of spoken Chinese based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. It is the official language of Mainland China. |

| where | Chinese is spoken in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore and other areas with historic immigration from China.It is usually spoken at home, between friends and relatives, entertainment, etc. | Mandarin: Pǔtōnghuà(普通话)It is a standardized form of spoken Chinese based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. It is the official language of Mainland China. |

| who | Chinese is spoken by the Han majority and many other ethnic groups in China. Nearly 1.2 billion people speak some form of Chinese as their first language. | Mandarin is spoken by more than 1 billion people. 70% of the Chinese people speak Mandarin and it is the largest spoken dialect in China. |

| where | Chinese can be traced back over 3,000 years to the first written records, and even earlier to a hypothetical Sino-Tibetan proto-language. | Mandarin is standardized by the “National Character Reform Conference” in 1955. |

| written | 1. Simplified system: Vocabulary which is the same as Mandarin. 2. Traditional system: Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Chinese speaking communities (except Singapore and Malaysia) outside mainland China. 3. Dialectal characters: Cantonese and Hakka, or vocabulary which is considered archaic or unused in standard written Chinese. | Simplified Chinese character system. |

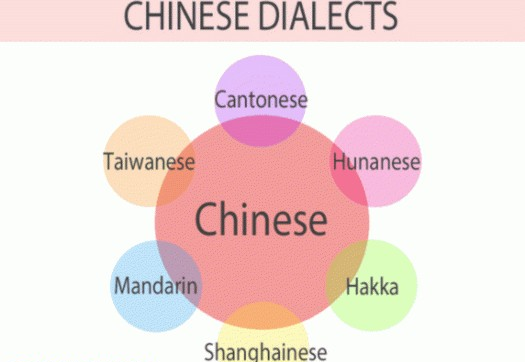

How many dialects of Chinese?

Chinese dialects are native language variations not mutually intelligible with Mandarin (Putonghua), despite sharing the same written characters. They reflect China’s vast cultural diversity: over 100 dialects exist, grouped into 7 major families (e.g., Mandarin, Yue, Wu). While Mandarin is the national standard, dialects like Cantonese (Guangdong) and Shanghainese (Shanghai) thrive as cultural symbols.

Iconic Dialects: Stories & Sounds

① Cantonese (Yue) – The “Hong Kong Superstar”

- Where: Guangdong province, Hong Kong, global Chinatowns (60M speakers).

- Why cool:

- 9 musical tones (e.g., “三” (saam1) vs. “心” (sam1) differ by tone and final consonant).

- Movie magic: In Infernal Affairs, Tony Leung’s “吔屎啦你!” (Jik6 si2 la1 nei5! “Eat shit!”) is pure Cantonese aggression—untranslatable to Mandarin.

- Food culture: “饮茶” (jam2 caa4, yum cha) isn’t just “drink tea”—it’s dim sum brunch culture.

- Fun fact: Cantonese was 差点成为 China’s national language in 1912 (lost by 1 vote to Mandarin!).

② Shanghainese – The “Velvet Tongue”

- Where: Shanghai, Zhejiang (14M speakers).

- What stands out:

- Gliding tones like a violin: “阿拉” (ngu1 la1, “we”) slides smoothly, unlike Mandarin’s sharp “我们” (wǒ men).

- Street wisdom: “买酱油” (mae6 tsiang4 yoe2) isn’t just “buy soy sauce”—it means “mind your own business” (from a 1990s TV joke).

- Fashion slang: “嗲” (tia3, cute/adorable) became a Shanghai identity symbol, even used in Mandarin today.

- Hard part: 入声 (short “-h” endings): “一” (iq) sounds like a quick breath, absent in Mandarin.

③ Sichuanese (Southwestern Mandarin) – The “Comedy Dialect”

- Where: Sichuan, Chongqing (120M speakers—bigger than France!).

- Why loved:

- Humorous rhymes: “巴适” (ba1 si2, comfy) and “安逸” (an1 yi2) make daily life sound cheerful.

- Food culture: “火锅” (ho2 guo1, hotpot) is universal, but “摆龙门阵” (bai3 nong2 men2 zhen4, gossip) is uniquely Sichuanese storytelling.

- Trick: Tone sandhi—“你好” (ni3 hao3) becomes “li2 hao3” in casual speech, confusing Mandarin learners.

④ Hokkien (Minnan) – The “Global Maritime Dialect”

- Where: Fujian, Taiwan, SE Asia (80M speakers).

- Superpower:

- Ancient roots: “飞” (hui1) 保留 Old Chinese “phui,” matching Japanese “hī” (飛ぶ).

- Pop culture: Jay Chou’s song “志明與春嬌” (Cì-bêng hî Chhun-kiu) uses Hokkien slang for unrequited love.

- Phrase: “有影无?” (ū-iánn-bô? Really?) is a staple in Taiwanese dramas.

Here’s an expanded comparison table with Mandarin, Cantonese, and Shanghainese .

| English | Mandarin | Cantonese | Shanghainese |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello | 你好 (nǐ hǎo) | 你好 (néih hóu) | 侬好 (non hau) |

| Thank you | 谢谢 (xièxie) | 多謝 (dō jeh) | 谢谢 (xia xia) |

| How are you? | 你好吗?(nǐ hǎo ma?) | 你好嗎?(néih hóu ma?) | 侬好伐?(non hau va?) |

| My name is | 我叫… (wǒ jiào…) | 我叫做… (ngóh giǔ jouh…) | 我叫… (ngu ciau…) |

| Goodbye | 再见 (zàijiàn) | 再見 (joi gin) | 再会 (tse we) |

| Good morning | 早上好 (zǎoshang hǎo) | 早晨 (jóu sàhn) | 早浪好 (tsau lang hau) |

| Good night | 晚安 (wǎn’ān) | 早唞 (jóu táu) | 夜到好 (ya tau hau) |

| Sorry | 对不起 (duìbuqǐ) | 對唔住 (deui m̀h jyuh) | 对勿起 (te veq chi) |

| Please | 请 (qǐng) | 請 (chéng) | 请 (chin) |

| How much? | 多少钱?(duōshao qián?) | 幾多錢?(géi dō chín?) | 几钿?(ci di?) |

| Eat | 吃 (chī) | 食 (sihk) | 喫 (chieq) |

| Water | 水 (shuǐ) | 水 (séui) | 水 (sy) |

| Friend | 朋友 (péngyou) | 朋友 (pàhng yáuh) | 朋友 (bang yeu) |

| Home | 家 (jiā) | 屋企 (ūk kéi) | 屋里厢 (oq li shian) |

Why Dialects Matter Today?

- Cultural survival: In Shanghai, only 38% of kids speak Shanghainese fluently (2023 study)—schools now teach dialect nursery rhymes.

- Business edge: Guangdong companies prefer Cantonese speakers for Hong Kong/Macau deals.

- Identity: Taiwan’s Hokkien activism shows dialects=pride—even K-pop group EXO’s Chen raps in Hokkien!

- Dialects are China’s “unofficial languages of the heart.” Yes, they’re harder than Mandarin—like learning jazz after piano—but worth it for the jokes, songs, and grandma’s stories. As a Cantonese saying goes: “学会广州话,走遍天下都不怕” (Learn Cantonese, fear no journey).

The Best Way to Learn Mandarin Chinese

Learning Mandarin isn’t about mastering characters or tones in isolation – it’s about building a relationship with the language. As a teacher of 12 years, I’ve seen students thrive when they blend structure with play, and language with culture. Below are 7 evidence-based methods, that work for beginners to intermediate learners.

1. Master Tones First – with Music and Movement

Mandarin’s 4 tones (e.g., mā = “mother,” má = “hemp”) are its biggest hurdle – but also its secret weapon.

- Teach tones as music: Hum melodies for each tone (e.g., high flat for 1st tone, rising for 2nd). Chant phrases like nǐ hǎo (2nd + 3rd tone) while clapping rhythms.

- Act them out: For 3rd tone (ǎ), squat and stand up slowly (“dipping” tone). For 4th (à), chop downward with your hand. Kinesthetic learning boosts retention by 70% (MIT study).

- Daily 5-minute drills: Start with 10 phrases like bā ge (8 brothers – 1st + 1st tone) and bà ge (8 songs – 4th + 1st). Record yourself and compare to native speakers (use YouTube clips of kids’ shows).

Why it works: Tones define meaning – mispronouncing mǎ (horse) as má (hemp) changes sentences. Early mastery prevents bad habits.

2. Speak from Day 1 – Even Badly

Too many learners delay speaking, fearing mistakes. But active practice builds neural pathways.

- “Kitchen Mandarin”: Label 10 items (冰箱 fridge, 鸡蛋 egg) and narrate cooking: “我现在打鸡蛋。放盐吗?” (I’m cracking an egg. Add salt?) Talk to yourself – no judgment!

- Street phrases first: Learn 请问… 在哪里? (Excuse me, where is…?) and 多少钱? (How much?) for real-life use. Practice with stall vendors during grocery runs – most locals love helping learners.

- Error tolerance: Keep a “Mistake Journal.” Note funny mix-ups (e.g., saying 买飞机 “buy airplane” instead of 买机票 “buy ticket”) – laughter reinforces memory.

Teacher tip: Set a “10-sentence rule” daily. Even simple phrases like 今天天气好 (Nice weather today) count.

3. Embed Vocabulary in Stories and Routines

Words stick when tied to emotions or rituals.

- “Family stories”: Ask grandparents to share childhood tales in Mandarin (record them!). Learn words like 捉迷藏 (hide-and-seek) and 压岁钱 (lucky money) through context.

- Daily routines as lessons: Use morning rituals: 刷牙 (brush teeth), 煮咖啡 (brew coffee). Create a “Morning Routine Chart” with drawings and characters – review while brushing.

- Food as vocabulary: Cook a Chinese dish (jiaozi, congee) and learn verbs: 切 (chop), 搅拌 (stir), 煮 (boil). Pair with a phrase: 妈妈教我包饺子 (Mom taught me to make dumplings).

Why it works: The brain remembers stories 22x better than isolated words (Harvard research). Linking language to senses (taste, touch) deepens retention.

4. Read “Messy” Chinese – Signs, Comics, and Text Messages

Forget perfect textbooks – real-life reading builds grit.

- Street sign scavenger hunts: Photograph 路牌 (road signs), 菜单 (menus), 广告 (ads). Look up 5 new characters weekly (e.g., 医院 hospital, 地铁 subway).

- Comics and kids’ books: Read 阿罗系列 (Arrow the Boy) or 西游记 (Monkey King) simplified versions. Circle unknown words, guess meanings from pictures, then look them up.

- Text message practice: Chat with a Chinese friend using 50% characters, 50% pinyin. Ask them to reply in both – e.g., nǐ xǐhuān kàn shénme diànyǐng? 你喜欢看什么电影?

Pro tip: Start with 5-minute daily reading. Progress to 15 minutes – consistency beats intensity.

5. Live the Culture – Celebrate Festivals and Folk Songs .

Language is a window to culture – embracing it makes learning joyful.

- Festival immersion: For Mid-Autumn Festival, make mooncakes while learning 团圆 (family reunion) and 嫦娥 (Moon Goddess). Sing 明月几时有 (How long has the bright moon been around?) – melody aids memory.

- Folk games: Play 丢手绢 (dodge the handkerchief) or 猜灯谜 (lantern riddles) with local communities. Learn phrases like 快点! (Hurry up!) and 我赢了! (I win!).

- TV without subtitles: Watch 动物世界 (Animal World) – slow speech, clear visuals. Repeat narrator phrases: 这是一只熊猫。它住在中国。 (This is a panda. It lives in China).

Why it works: Cultural engagement creates emotional bonds with the language – crucial for long-term motivation.

6. Write “Ugly” Chinese – Journals and Postcards.

Writing reinforces muscle memory – even if messy.

- “3-sentence journal”: Every night, write 3 sentences: 今天我学了 “谢谢”。明天想吃面条。 (Today I learned “thank you.” Tomorrow I want noodles). Don’t worry about perfect characters – focus on meaning.

- Postcard practice: Send postcards to Chinese friends, mixing characters and doodles. Example: [画太阳] 今天天气很热!你那里呢? (It’s hot today! How about your place?)

- Character art: Trace characters in sand, rice, or with a finger – kinesthetic writing helps remember strokes.

Anyway, The best way to learn Mandarin is to live it, not just study it. Tones become music, mistakes become stories, and characters become windows to a 5,000-year-old culture. As Confucius said, “知之者不如好之者,好之者不如乐之者” (To know it is not as good as to love it; to love it is not as good as to delight in it).

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!FAQs about is Mandarin Chinese

1, Should I learn Chinese or Mandarin?

Learn Mandarin first – it’s the official language of Chinese. While “Chinese” includes many Chinese dialects (like regional accents), Mandarin (Putonghua) is China’s national language – spoken in schools, TV, and 95% of daily life. It lets you:

Order food, ask directions, or chat with locals anywhere in China (instant use!).

Read simplified characters (used in 90% of books/websites).

Build a foundation for dialects later (if you want Cantonese).

Why not start with dialects? They’re like local spices – fun but hard to use universally. Mandarin is your “bridge” to 1.3B speakers.

2, Is Mandarin Chinese Hard to Learn?

Mandarin’s difficulty depends on your native language and linguistic exposure. For English speakers, the Foreign Service Institute classifies it as a Category IV language (~2,200 hours to proficiency). Key challenges include:

- Tones: Mastering pitch variations (e.g., mā vs. mǎ) is critical, as mispronunciations alter meanings.

- Characters: Memorizing 3,000+ logograms and distinguishing simplified/traditional scripts demands time.

- Grammar Nuances: While lacking verb conjugations or plurals, measure words (e.g., 一个苹果, “one apple”) and context-heavy syntax require practice.

However, Mandarin’s straightforward tenses and growing resources (apps, media) ease learning. Prioritizing spoken Mandarin with Pinyin first can accelerate progress. With consistent effort, it’s challenging but achievable.

3,Is Mandarin and Cantonese the Same?

No, Mandarin and Cantonese are distinct varieties of Chinese. While both use Chinese characters for writing, they differ fundamentally:

- Mutual Intelligibility: Spoken forms are mutually unintelligible. A Mandarin speaker cannot understand Cantonese without study.

- Tones: Mandarin uses 4 tones; Cantonese has 6–9 tonal contours, altering word meanings more intricately.

- Vocabulary: Terms diverge (e.g., “thank you” is xièxie in Mandarin vs. dō jeh in Cantonese).

- Geographic Roles: Mandarin is China’s official language; Cantonese dominates Guangdong, Hong Kong, and diaspora communities.

Though rooted in Middle Chinese, centuries of regional evolution and political standardization (e.g., simplified characters for Mandarin) have solidified their differences. They coexist as culturally significant but separate branches of the Chinese language family.

4, Is Mandarin the Most Spoken Language?

Mandarin Chinese is the most spoken native language globally, with over 1.1 billion native speakers, primarily in mainland China, Taiwan, and Singapore. However, when considering total speakers (including second-language learners), English edges ahead due to its role as a global lingua franca. Mandarin’s dominance stems from China’s population size and state policies enforcing it as the official language in education, media, and governance. While other Chinese dialects like Cantonese (80 million speakers) or Shanghainese (14 million) thrive regionally, Mandarin’s unified status ensures its unparalleled reach. Globally, it ranks among the most strategic languages for business and diplomacy, yet its complexity—tones, characters—keeps it challenging for learners.

In short: yes for native speakers, no for total usage.

Conclusion

The term “Chinese” refers to the Sinitic language family, a diverse group of mutually unintelligible dialects like Cantonese, Shanghainese, or other local dialect, each with distinct tones, vocabulary, and grammar. Mandarin, however, is the standardized official language of China, rooted in the Beijing dialect and spoken by over 1.1 billion people. While all Chinese varieties share logographic characters (written as simplified or traditional scripts), their spoken forms diverge drastically—Cantonese, for example, uses 6–9 tones versus Mandarin’s 4-tone system and retains archaic pronunciations lost in Mandarin.

The Chinese government enforces Mandarin as the national language through education, media, and law, marginalizing regional dialects. Yet, dialects persist as cultural cornerstones: Cantonese dominates Hong Kong’s cinema, Shanghainese thrives in local communities, and Hokkien connects overseas diaspora. In essence, Mandarin is a unified political tool, while “Chinese” celebrates a tapestry of linguistic heritage—both vital to understanding China’s identity.

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!

My name is liz and I graduated from the University of International Business and Economics. I have a strong background in fields such as education, economics, artificial intelligence, and psychological aspects, and I have dedicated my career to writing and sharing insights in these areas. Over the years, I’ve gained a wealth of experience as an English guest blogger, writing for a number of platforms. Currently, I write for WuKong Education, which focuses on sharing learning experiences with young readers around the world. My goal is to help more teenagers gain more knowledge through my experience and research.

![Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide] Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/school-2353406-520x293.jpg)

![2025 AMC 8: Problems Solutions, Answers Key, Score [With Free PDF] 2025 AMC 8: Problems Solutions, Answers Key, Score [With Free PDF]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/image-560-520x293.png)

![35 Top Ways to Say Happy New Year in Chinese and Cantonese [Auido Pronunciation] 35 Top Ways to Say Happy New Year in Chinese and Cantonese [Auido Pronunciation]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/image-285-520x293.png)

Comments0

Comments