How to Say No in Chinese: 10 Ways in Mandarin

If you are new to Mandarin Chinese language, you will most likely want to learn some basic Chinese words and phrases so that you can communicate better with native speakers. After “Hello”, “Thank you” and “My name is”, learning to say and write “No” in Chinese should be your top list.

You may be surprised that the person helping you learn Mandarin may not immediately teach you to say “No” in Chinese. This is because, unlike most other languages, there are no words in Chinese that directly correspond to the English “Yes” or “No,” meaning there is no direct Chinese equivalent.

In English, we combine “No” with different words to give a negative answer, such as “No, I don’t” or ” No, I can’t”. You can do the same with “No” in Chinese, for example, “don’t want” ( “bù yào” “bù xiǎng” ) or “can’t” ( “bù xíng”, or “bù néng” ) to give a negative answer.

So does this mean that saying “No” in Chinese is complicated? Not really! Once you learn and understand the patterns and workings of the language, you will be able to use “Refuse” or “Disagree” just like native speakers. And how do you say “no” or “refuse” in Mandarin? The answer is that it depends on the context.

In this article, we will introduce 10 ways to say “No” in Mandarin, which will help you understand how “No” is used in the Chinese language from many angles!

The Basics of Saying No in Chinese Language

Saying no in Chinese can be a complex task, especially for beginners. Unlike English, Chinese does not have a direct translation for the word “no.” Instead, the language uses various Chinese words and phrases to convey negation, depending on the context and situation. For instance, you might use “bù” (不) to negate a verb or adjective, or “méiyǒu” (没有) to indicate the absence of something. Understanding the basics of saying no in Chinese is essential for effective communication and avoiding misunderstandings. By learning the different ways to express negation, you can respond appropriately in various scenarios, whether you’re declining an offer, refusing a request, or simply stating that something is not true.

10 Best Ways to Say No in Mandarin Chinese

One of the unique aspects of the Chinese language is that it does not have a direct translation for the English word “no.” This means that learners of Chinese must understand the different ways to express negation in various contexts. For example, the phrase “bù shì” (不是) is used to say “no” in response to a question, while “bù yào” (不要) is used to decline an offer or request. The absence of a single word for “no” requires learners to be more mindful of the context in which they are responding negatively. This nuanced approach can initially seem challenging, but it ultimately leads to more precise and contextually appropriate communication.

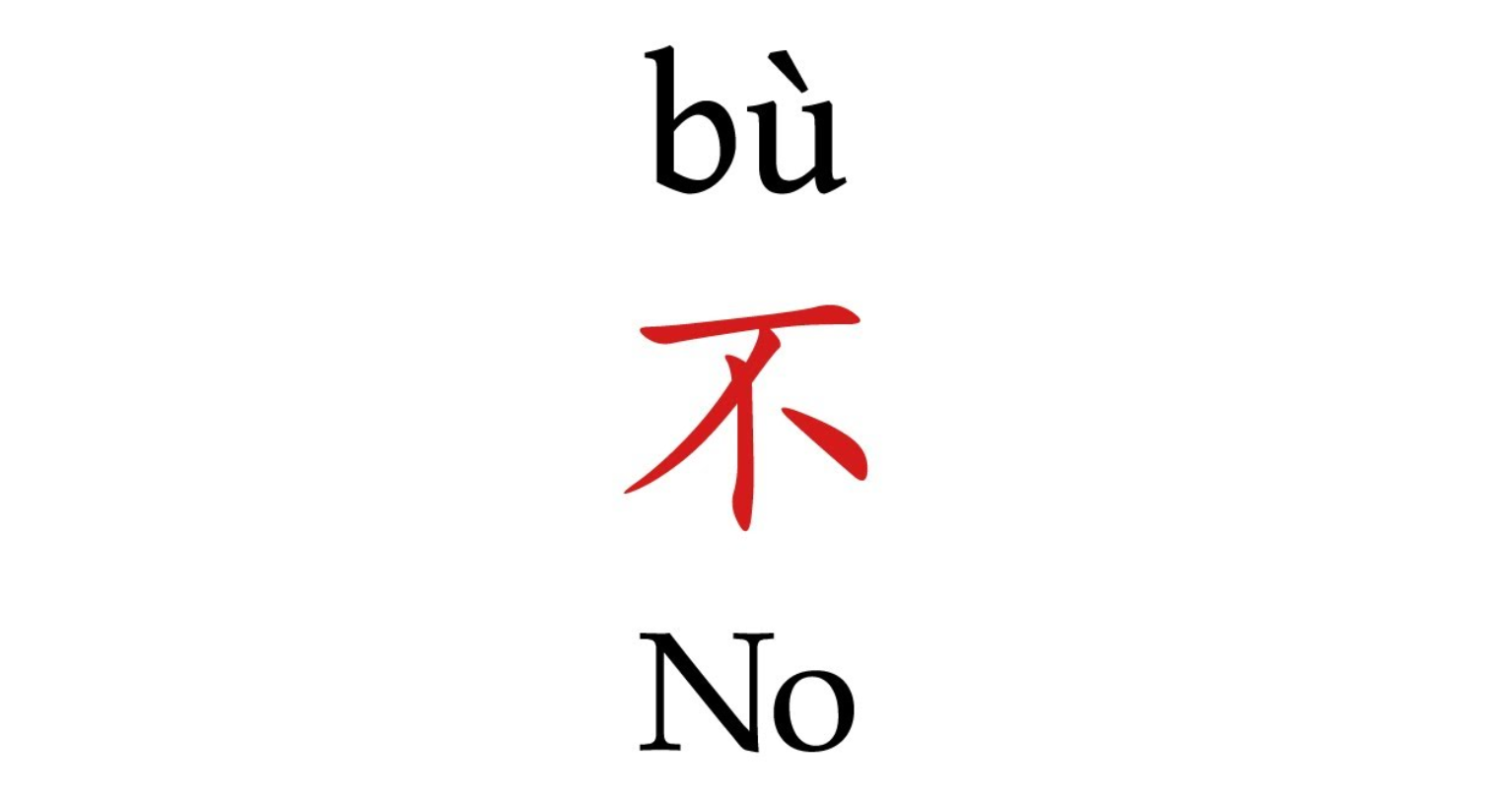

1. 不 | bù | no in Mandarin Chinese

This is the most common way to say “no” in Chinese, as well as the most direct and simplest way to say the opposite. This negative word is rarely used on its own; it is almost always used as a negative prefix with other words that might otherwise come across as stiff.

If you want to use “不” (bù) in a sentence, here are some more examples of how to use it:

- 他不会说中文 ( tā bù huì shuō zhōngwén) He doesn’t speak Chinese.

- 我不喜欢这本书 ( wǒ bù xǐ huān zhè běn shū) I don’t like this book.

- 我们不想去公园 ( wǒmen bù xiǎng qù gōng yuán) We don’t want to go to the park.

In English or other languages, you simply use the answer “no”, whereas in Mandarin, you use a sentence. This is not complicated; use it a few more times and the word will out before you can stop them.

Another common way to express negation in Chinese is by using “没有” (méiyǒu). The literal translation of 没有 (méiyǒu) is ‘not have’ or ‘don’t have,’ which helps to clarify its usage in expressing negation in Mandarin.

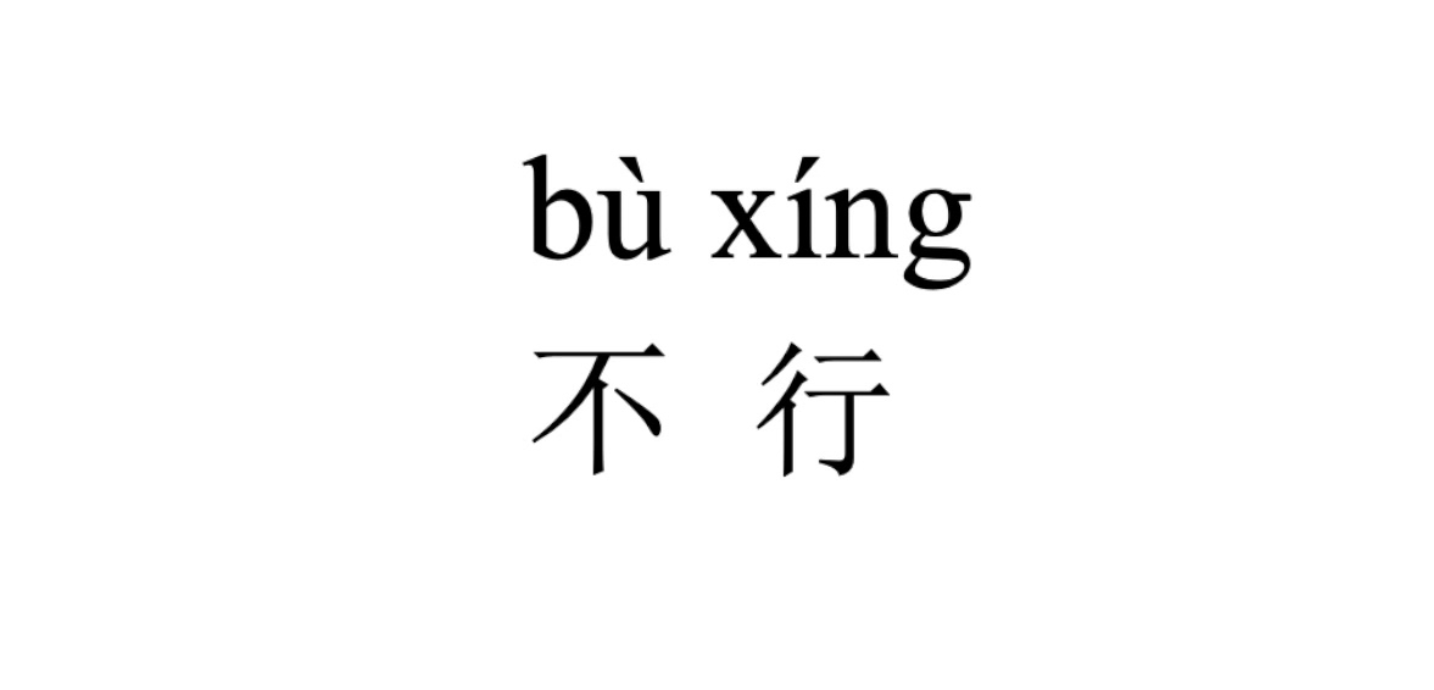

2. 不行 | bù xíng | not alright; not OK

行 (xíng) means “good” or “can” in Chinese. Adding “不” (bù) in front of “行” (xíng) turns it into a negative meaning.

In the present tense, 不 (bù) is used to express negation, such as in the structure 不 + verb for both present and future contexts.

不行 (bùxíng) can be roughly translated as “not good”, “not all right” or “not OK”

For example, if someone asks you if a certain time is good for you to do something and your schedule is not quite right, you can say “这个时间不行 (zhè gè shí jiān bù xíng)”, which directly translates to “This is not ok”. Here are more examples:

- 你能借我五百元吗? (Nǐ néng jiè wǒ wǔ bǎi yuán ma?) Can you lend me 500 RMB?

- 不行。(Bùxíng.) No way.

- 你能在明天之前完成作业吗? (Nǐ néng zài míng tiān zhī qián wán chéng zuò yè ma?) Can you finish the homework by tomorrow?

- 不行。(Bùxíng.) Impossible.

- 这里可以停车吗? (Zhè lǐ kě yǐ tíng chē ma?) Is it okay to park here?

- 不行. (Bùxíng.) No. (It’s not allowed.)

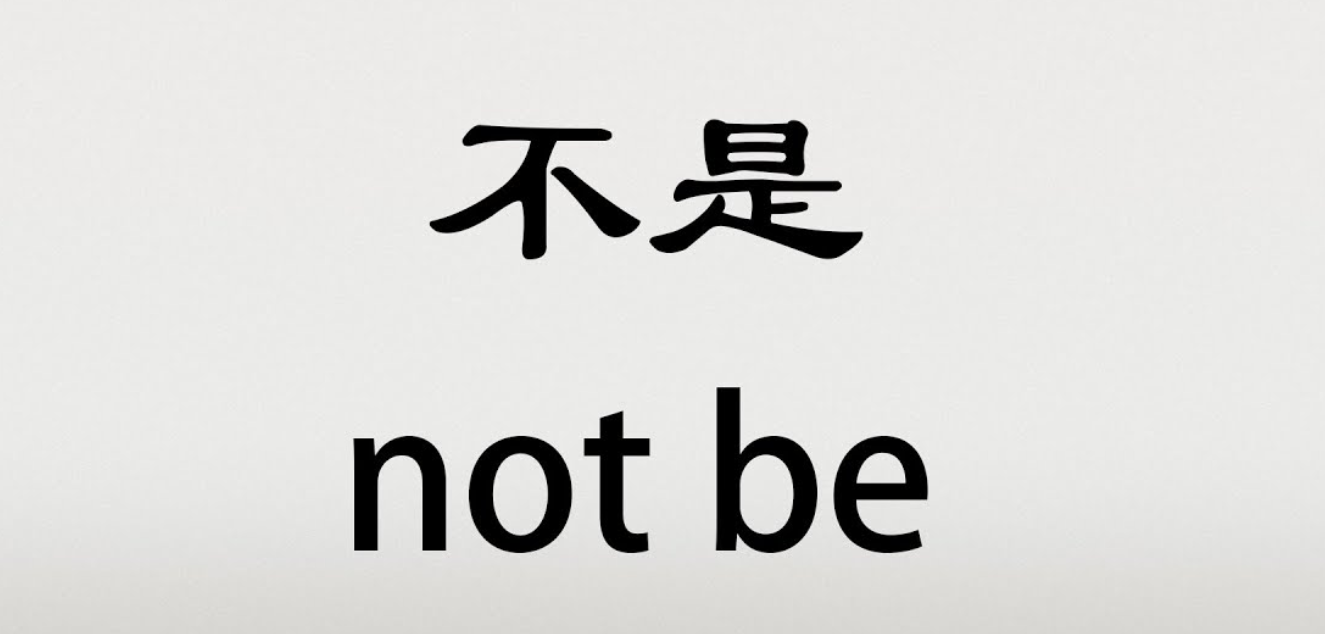

3. 不是 | bùshì | no; not be; is not

One of the most common ways to say “yes” in Chinese is “是” (shì, is). Therefore, when you add “不” (bù, not; not) in front of “是”(shì) at the same time, you are conveying the meaning of “no”. In future tense contexts, ‘不’ (bù) can also be used to negate future actions, as Mandarin Chinese does not have a dedicated future tense form and relies on context to convey future intentions.

When you say “不是” (bùshì), you are saying “no” or “is not”.

Usually, 不是(bùshì) is used to disagree or question the truth of someone’s words and to express denial.

If someone asks you a question to confirm something, then you can answer or refute it with “不是” (bùshì) as a way of saying that what he said is not true.

不是 (bùshì), which in English means “no; is not; not be,” is used to negate adjectives, verbs, and nouns. People use 不是 (bùshì) when they want to say that something is not correct or true. For example, “这个不是我的书” (zhège bùshì wǒde shū) which means “This is not my book.” And Here are more examples:

| Speaker | Chinese汉字 | Pinyin拼音 | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 这是你的笔吗? | Zhè shì nǐ de bǐ ma? | Is this your pen? |

| B: | 不是。 | Bùshì. | No, it’s not. |

| A: | 你是学生吗? | Nǐ shì xué shēng ma? | Are you student? |

| B: | 不是。 | Bùshì. | No, I’m not. |

“不是的” (bùshìde) is another phrase that can be used to mean ‘no’ in Chinese. It sounds a bit more informal and casual than “不是” (bùshì), but the two are used almost identically and are more or less interchangeable.

For example:

| Speaker | Chinese汉字 | Pinyin拼音 | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 这个礼物是给小朋友的吗? | Zhè gè lǐ wù shì gěi xiǎo péng yǒu de ma? | Is this gift for a child? |

| B: | 不是的。 | Bùshìde. | No, it isn’t. |

A tip: The words “不” (bù) and “是” (shì) are both pronounced in the fourth tone on their own. However, if the tone of the character after “不” (bù) is also in the fourth tone, then the pronunciation of “不” (bù) will change, and you will need to raise the tone so that it temporarily becomes the second tone.

Therefore, even though the pinyin for 不(bu) is bùshì, it should be pronounced as búshì.

4. 不要 | bùyào | no; don’t want

不要 (bùyào) is a common way to express rejection or exclusion in Mandarin Chinese. It is used to express not wanting or not wanting to do something. Another polite way to refuse offers is by using 不用 (bùyòng), which maintains a respectful tone.

The phrase can be used in a variety of contexts to express negation or rejection directly and politely.

- For example, if someone asks you if you want a cup of coffee, you can say “No, I don’t (want to).” “不要“ (bù yào).

Tip: This phrase is more commonly used to refuse things that don’t exist yet or things that the other person wants to offer you, rather than those things they already have.

5. 不可以 | bùkěyǐ | cannot; may not

In daily life or at work, we can’t always let other people be able to do everything they want for us. Sometimes we have to say “no” more forcefully, and in such cases we can use “不可以” (bù kě yǐ), which translates directly to “cannot; can’t” in English. In this case, we can use “不可以” (bù kě yǐ).

For example, if someone asks you for something and you don’t want to give it to him, you can say “这个不可以(zhège bù kě yǐ)”, which directly translates to “you can’t use this”. Or when a person wants to smoke and asks you if it’s okay, you can say “不可以”(bù kěyǐ), which means “No, you can’t smoke here”.

Other examples are as follows:

- 你不可以进来 (nǐ bù kě yǐ jìnlái) You can’t come in.

- 我不可以告诉你 (Wǒ bù kě yǐ gàosu nǐ) I can’t tell you.

- 这个答案不可以用 (zhège dá’àn bù kě yǐ yòng) This method cannot be used.

6. 不对 | bùduì | not correct; incorrect

If you are discussing something with someone from China or with someone who speaks Chinese, “不对” is a phrase you should know. Let’s say you’re arguing with native Chinese speakers about the nature of an issue, and you want to convey that someone’s opinion is incorrect, you can use “不对”(bù duì), which means “incorrect or not correct” in English.

For example, if your friend says 5+1 = 7, then you can say “bùduì” (不对). It means “This is incorrect”. Here are more examples:

| Speaker | Chinese汉字 | Pinyin拼音 | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 明天的会议在下午两点,对不对? | Míngtiānde huìyì shì xiàwǔ liǎngdiǎn, duìbùduì? | Tomorrow’s meeting is at 2 pm, right? |

| B: | 不对,明天的会议是下午三点。 | Bùduì, míngtiānde huìyì shì xiàwǔ sāndiǎn. | No, tomorrow’s meeting is at three o’clock. |

7. 不会 | buhui | no; cannot; will not

If you want to say “what you can do” in Chinese, that is, those things you have learned how to do, then the word “会” (huì) is the one you should use. “会” huì is the Chinese word that most directly corresponds to the English word ‘can’. Therefore, you can add “不” to “会” which is the phrase “不会 bùhuì” to show that you can’t do something:

- 我妹妹不会游泳. Wǒ mèimei bùhuì yóuyǒng. My little sister can’t swim.

- 你会说中文吗?Nǐ huì shuō zhōngwén ma? Can you speak Chinese?

- 不会. Bùhuì. No, I can’t.

- 你吃过臭豆腐吗?Nǐ chīguò chòu dòufu ma? Have you ever eaten stinky tofu?

- 没吃过. Méi chīguò. No, I haven’t eaten stinky tofu.

As another reminder, the correct pronunciation of “不会” here is “bú huì”, not “bù huì” as in pinyin, and it’s not all falling tone.

Somewhat confusingly, although “会”(huì) means “can”, it is also used to refer to something that is going to happen, which is the English equivalent of “will”. Therefore, you can combine “会“ (huì) with other verbs or adjectives to express something that will happen in the future. Similarly, you can use “不会” (bùhuì) to express something that won’t happen, or to give a negative answer to a question about the future:

- 你觉得今天会很热吗? (Nǐ juédé jīntiān huì hěn rè ma?) Do you think it will be hot today?

- 不会, 看起来会下雨. (Bùhuì, kànqǐlái huì xiàyǔ.) No, it looks like it’s going to rain.

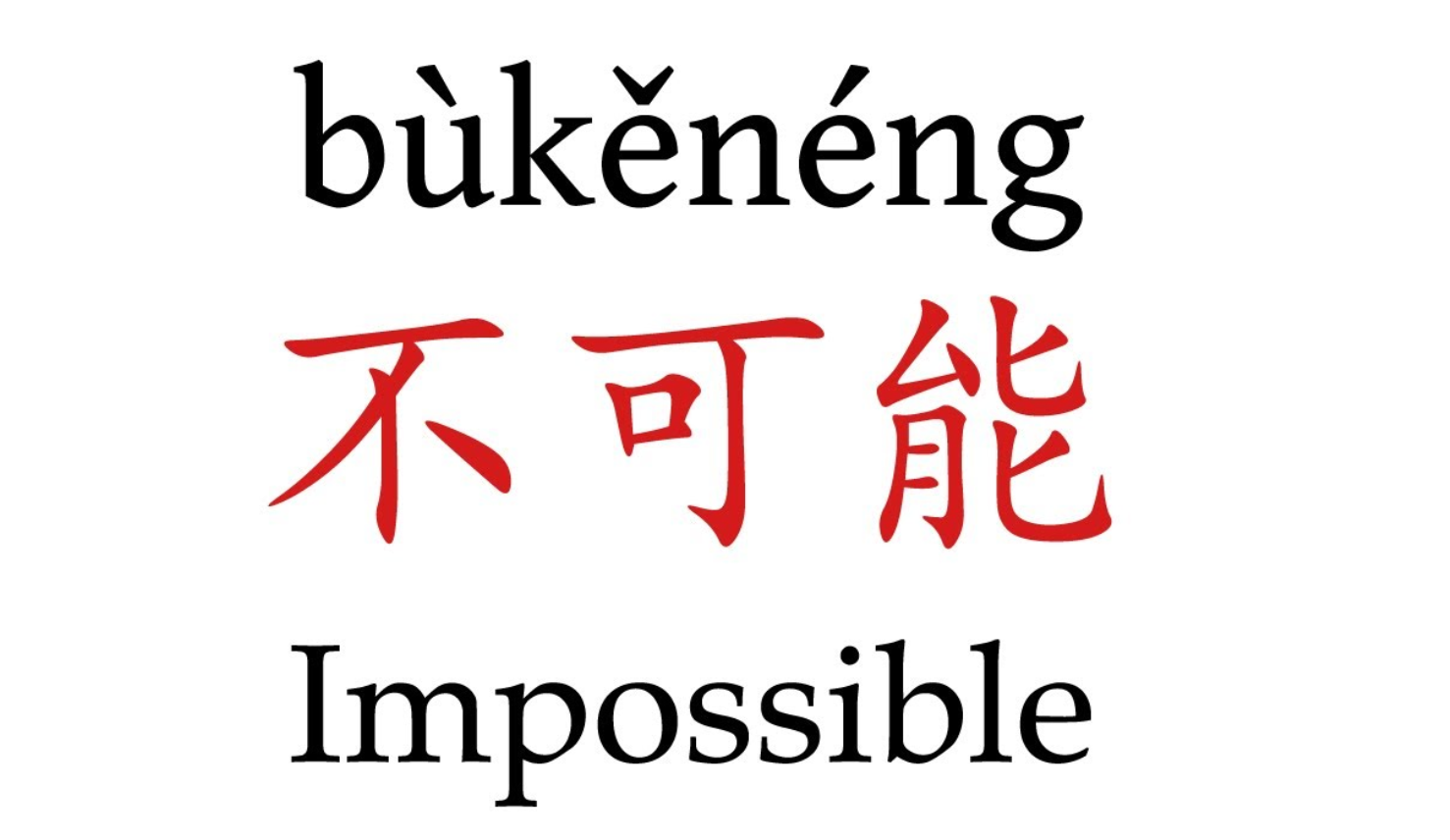

8. 不可能 | bùkěnéng | impossible; not possible

Do you want to learn a stronger negative answer in Mandarin Chinese? The answer is – “不可能” (bù kěnéng).

This phrase is made up of the negatives bù (不) and kěnéng (可能), which in Chinese means “maybe “ or “possibly”.

Combine them and you get “不可能” (bù kěnéng), which means “impossible”, “no way” or “not possible”.

| Speaker | Chinese汉字 | Pinyin拼音 | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 我明天可以借你的车吗? | wǒ míngtiān kěyǐ jiè nǐde chē ma? | Can I borrow your car tomorrow? |

| B: | 不可能!上次你把车刮坏了! | Bù kěnéng! Shàngcì nǐ bǎ chē guāhuàile! | No, that’s impossible! You scratched the car last time! |

Use “不可能” (bùkěnéng) when you want someone to know that what they are saying is completely impossible.

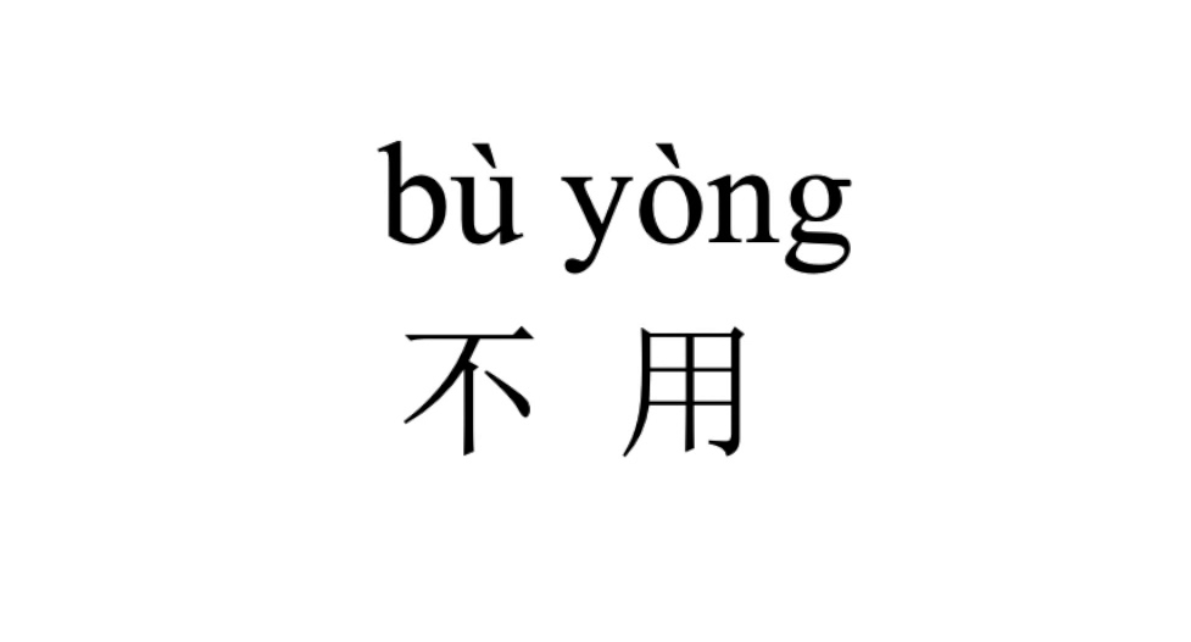

9. 不用 | bùyòng | no need; no use

The phrase “不用” (bùyòng) means “no use” or “no need”, but the literal meaning has little to do with its usage in Chinese. In Mandarin Chinese, “不用” (bùyòng) is a good way to refuse someone’s help. If you want to know how to say “No, thank you” in Chinese, “不用” (bùyòng) is the most convenient phrase to use.

Although “不用” (bùyòng) also contains “不” (bù), it is difficult to use its components to guess its meaning.

In Chinese, “用” (yòng) means “to use” or “to be useful”, so “不用” (bùyòng) can be directly translated as “not used” or “not useful”. However, this direct translation does not reveal well its actual meaning, i.e. “no, thanks”.

Generally speaking, “不用” (bùyòng) is used to express polite refusal.

There are more examples in the table below:

| Speaker | Chinese汉字 | Pinyin拼音 | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 你需要帮忙吗? | Nǐ xūyào bāngmáng ma? | Do you need help? |

| B: | 不用。 | Bùyòng. | No, thanks. |

| A: | 我送你回家吧。 | Wǒ sòng nǐ huí jiā ba. | Let me take you home. |

| B: | 不用(了)~ | Bùyòng(le)~ | No, thanks~ |

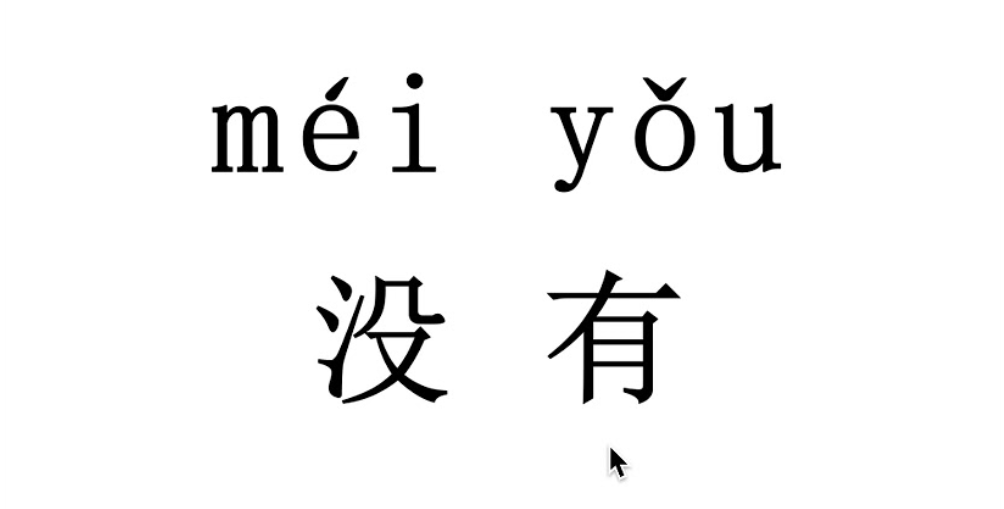

10. 没有 | méiyǒu | no; don’t have; have not

Unlike all the other Chinese expressions for “no” that we have discussed so far, the word “no” (méiyǒu) itself does not contain the word “no” (bù).

But don’t be confused by this fact. “没有” (méiyǒu) is one of the most common ways to say ‘no’ in Mandarin.

If we divide “没有” (méiyǒu) into several parts, we get “没 (méi)” and “有 (yǒu)”. The former means “not” and the latter means “to have”. Thus, the direct translation of without (méiyǒu) is “not have”.

Unsurprisingly, one of the uses of “没有” (méiyǒu) is to tell someone that you don’t have something.

For example, if your friend asks you for a pencil and you don’t have one, you can say “我没有 (Wǒ méiyǒu),” which means “I don’t have a pencil.” Another example is when someone asks you “你吃了吗?” (nǐ chī le ma?), which means “Have you eaten?” You can answer “No.” (méi yǒu.) or “No, I haven’t eaten.” Here are more examples:

- 你有钱吗? (nǐ yǒu qián ma?) Do you have money?

- 我没有。 (Wǒ méiyǒu) I don’t have it.

- 你有笔记本电脑吗?(Nǐ yǒu bǐjìběn diànnǎo ma?)Do you have a laptop?

- 没有。(Méiyǒu)No (I don’t).

Some older people may not be familiar with the use of “没有” (méi yǒu), so they may use the word “没” (méi), which also means “no” in English. Although they are both used to mean “no”, the contexts are different. “没” (méi) is more direct, while “没有” would sound a bit more polite in its expression.

FAQs on How to Say No in Chinese

Q 1.How to say no in Cantonese?

Cantonese and Mandarin are both subordinated under the Chinese system, but they have different grammar.

- If you want to say “no” to indicate refusal, in Cantonese that would be “唔得”.

- If you want to say “no” in general (e.g. “No, not here”), it’s “唔係,唔喺度”.

- If you want to say “不好”, it is “唔好”.

The common Cantonese word for no is “唔”. You can add it between verb phrases and make them negative, such as 攞出嚟 – 攞唔出 / take it out – can’t take it out.

Q 2. What’s the correct fourth tone for the word “No” in Chinese?

Answer: When starting to learn Chinese, you should start out by mastering pinyin and the tones so you have a solid foundation for pronunciation. It is important to note that the word ‘不’ (bù) changes its tone from falling to a rising tone when followed by a fourth-tone character. After learning pinyin and tones, you’ll start learning words.

- 不 (bù) is a tone-changing character that you should pay special attention to.

There are four tones in Chinese, and technically a fifth tone: the first tone (high/flat), the second tone (rising), the third tone (low/flat), and fourth tone (falling), and the fifth “neutral” tone (toneless tone).

- In spoken language, the word “不” (bù) can be pronounced in the fourth, second, and sometimes neutral tones.

1: Fourth tone (bù)

The word “不” (bù) itself is the fourth tone in normal circumstances. And let’s look at a few examples:

- 不行 (bù xíng) – not alright

- 不喜欢 (bù xǐ huan) – don’t like it

2: Second Tone (bú)

The only time that 不 (bù) changes from the fourth tone to the second tone is when it is followed by another fourth-tone character – 不 (bù) will then change to the second tone. Let’s see a few common examples:

- 不会 (bú huì) – will not

- 不要 (bú yào) – to not want

3: Neutral Tone (bu)

不 (bù) can technically also be spoken as a neutral tone when used in potential complements, the “verb-not-verb” structure, and some set phrases with 不 (bù) in the middle.

Potential complements:

- 听不懂 (tīng bu dǒng) – cannot understand (by hearing)

- 做不了 (zuò bu liǎo) – cannot do

Verb-not-verb structure:

- …是不是… (shì bu shì) – is/are … or not

- …行不行… (xíng bu xíng) – is … OK or not

And set phrases:

- 对不起 (duì bu qǐ) – I’m sorry

Q 3. Can “不 bù” be used to Negate Verbs and Adjectives?

Answer: In Chinese, the character “bù” (不) is used to negate verbs and adjectives. This means that by adding “bù” to a verb or adjective, you can change its meaning to the opposite.

For example, “wǒ xǐ huān” (我喜欢) means “I like,” while “wǒ bù xǐ huān” (我不喜欢) means “I don’t like.” Similarly, “tā huì” (他会) means “he can,” while “tā bù huì” (他不会) means “he cannot.” Understanding how to use “bù” to negate verbs and adjectives is a crucial aspect of saying no in Chinese.

This simple yet powerful character allows you to respond negatively in a wide range of situations, making it an essential part of your Mandarin vocabulary.

Q 4. How to write No in Chinese language?

Answer:

Step 1: Strokes Breakdown: “不” consists of two strokes:

- First Stroke: A horizontal line from left to right.

- Second Stroke: A vertical line that starts at the top of the horizontal line and goes downwards, then curves to the left.

Step 2: Writing the Character:

- Start with the horizontal stroke, drawing a short line from left to right.

- Next, draw the vertical stroke starting at the left end of the horizontal line, going down, and then curving to the left.

Step 3: Practice:

- Repeat writing the character several times to become familiar with its shape and stroke order.

You can practice writing it on paper or use a digital tool that allows you to draw Chinese characters.

Summary

To say “no” in Chinese you need to master the correct pronunciation of words and tones to convey your message effectively. Those teaching Chinese often explain the cultural intricacies, such as the importance of using various phrases to express disagreement or refusal, which highlights the complexity of communicating ‘no’ in Chinese.

The most important thing to remember when saying “no” in everyday life is to be aware of the different meanings of each word and to pay attention to the tone of voice when saying “no”. If you are not sure which word to use in a particular situation, it is best to ask a native Chinese speaker or someone who teaches Chinese.

If you are interested in Chinese culture or want to improve your Chinese learning skills, Wukong Chinese courses are for you. We provide high-quality online Chinese teachers and exceptional content to make language learning easier and more fun and help you keep improving your Chinese learning.

With some practice, I’m sure you will be able to say “No” in Mandarin like a native Chinese speaker!

Learn authentic Chinese from those who live and breathe the culture.

Specially tailored for kids aged 3-18 around the world!

Get started free!Master’s degree from Yangzhou University. Possessing 10 years of experience in K-12 Chinese language teaching and research, with over 10 published papers in teh field of language and literature. Currently responsible for teh research and production of “WuKong Chinese” major courses, particularly focusing on teh course’s interest, expansiveness, and its impact on students’ thinking development. She also dedicated to helping children acquire a stronger foundation in Chinese language learning, including Chinese characters, phonetics (pinyin), vocabulary, idioms, classic stories, and Chinese culture. Our Chinese language courses for academic advancement aim to provide children with a wealth of noledge and a deeper understanding of Chinese language skills.

![Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide] Math League: Competitions, Challenges, and Achievements [2025 Full Guide]](https://wp-more.wukongedu.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/school-2353406-520x293.jpg)

Comments0

Comments